Written by Liberty Munson, Director of Psychometrics, Microsoft

In an earlier post, I laid the foundation for understanding psychometrics by defining the core tenet of psychometrics: to ensure that an evaluation is psychometrically sound: valid, reliable, fair, and meaningful. In this post, I want to talk about important practices that help ensure your evaluation is fit for its purpose.

Psychometrically sound evaluations are designed to minimize error and maximize our ability to predict behaviors or understand the test taker’s true “ability” in a specific content domain. An evaluation is more likely to be psychometrically sound if it follows industry best practices related to how it’s designed, developed, delivered, and maintained. However, the level to which programs adhere to these standards, or the psychometric rigor used, should depend largely on the conclusions (inferences) that they want to draw based on the results of the evaluation experience and the consequences of getting the inference wrong.

Psychometric Rigor

Psychometric rigor is driven by a wide variety of levers that can be pushed or pulled as needed depending on the stakes of the evaluation process. Some of these levers include the number and type of SMEs used throughout the process, the approach taken to each step of the process (there’s a best approach, a “good enough” approach, a bad approach, and likely approaches in between), and the level of the “questions” that are asked during the evaluation process (e.g., recall versus synthesis).

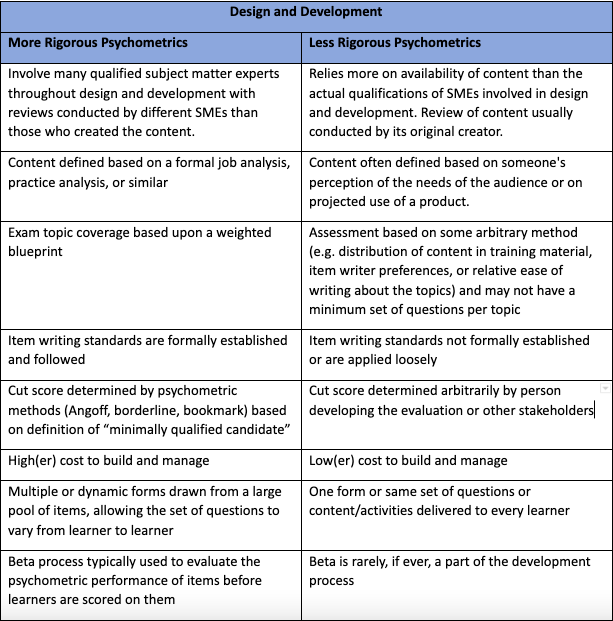

Design and Development

Designers of an evaluation can increase its content validity by conducting a formal analysis that identifies and defines the key elements of the domain to be evaluated. Basing the evaluation on this analysis increases the confidence with which inferences can be drawn about the evaluation-taker’s competence or proficiency (e.g., specific technical knowledge or skills, problem-solving ability, etc.). In many cases, this takes the form of a job-task analysis, competency model, or practice analysis. This analysis is usually done through focus group conversations with subject matter experts (SME) and is the foundation of the evaluation process. Every step that follows must tie back to what was identified during the analysis. In other words, everything that is assessed on the evaluation must clearly align to one or more of the attributes identified during that analysis. The rigor of this process can be adjusted as needed based on the inferences you want to be able to make from the results of the evaluation. Psychometrics comes into play in these decisions because including fewer or less-qualified SMEs or taking a shorthand approach to this analysis may change the what inferences can be made and the confidence with which they can be made, and may increase the risk that the inference is incorrect. Your approach to this analysis can include several psychometric levers that can be pushed as needed to meet business or programmatic needs.

In terms of development, less rigorous measurement experiences can use fewer or less-qualified SMEs to create and review the evaluation opportunities (e.g., questions asked, tasks performed) and may take different approaches to the creation and review processes. In addition, a smaller range of question types may be used, the question structure could be modified, a lower level of Bloom’s taxonomy assessed, and/or a beta experience may be eliminated. In addition, the passing score could be set arbitrarily although guidance from a psychometrician is always recommended—it’s rarely a good idea to set the passing score without some understanding of the implications of that choice.

Below is a table comparing more and less rigorous psychometric approaches to the different decisions that go into evaluation design and development. Note that this is based on a recent ITCC resource, Certifications and Learning Assessments: What are the Differences?

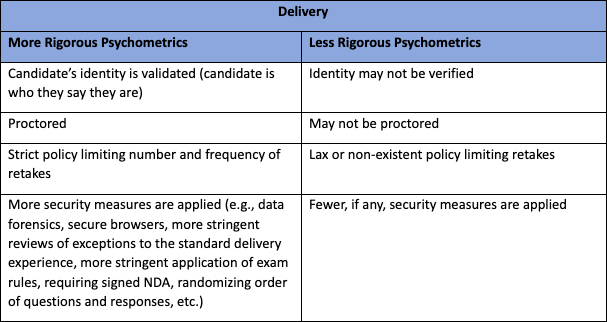

Delivery

Because differences in the measurement experience can affect the outcome, in higher stakes situations, more control is exerted over the evaluation delivery process. At minimum, the evaluation will be proctored and the test-taker’s ID will be verified. Some programs may add additional requirements, such as requiring their test takers to go to a test center. However, in lower stakes experiences, more variations in delivery can be tolerated; for example, the evaluation may be unproctored or recorded and reviewed later, ID may not be required, and so on.

Security is much more important in higher stakes experiences than lower stakes, in which few, if any, security measures may be applied.

These decisions are psychometric decisions because the inferences that can be made based on the result of the measure is affected. If you decide to proctor the exam, you are more certain that the person who passed the evaluation didn’t cheat in some way; if you check IDs, you are more certain that the person who passed is the same person who took the evaluation.

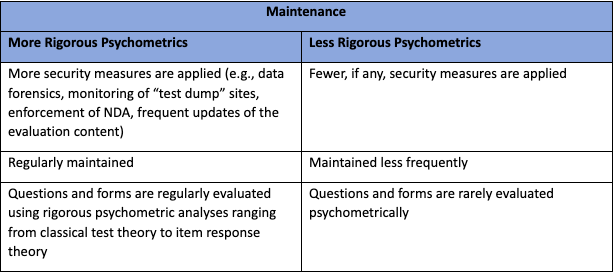

Maintenance

The evaluation should be regularly examined from a statistical perspective, using item-level analytics to ensure that the questions or tasks are at the appropriate level of difficulty and are differentiating between test-takers who are high or low on the attributes of interest. In a more rigorous evaluation, questions that perform poorly will be fixed or replaced. In addition, the accuracy, relevance, and appropriateness of question alignment to the content domain should be assessed on an ongoing basis. This includes regular reviews of the (job task) analysis that formed the basis of the evaluation and ensuring that the evaluation still assesses what it should be assessing.

These are other psychometric levers that can be pushed based on the stakes and inferences that you want to draw based on the outcome of the evaluation. For example, some types of evaluations can be reviewed less frequently—both the foundational analysis as well as from a statistical perspective — and reviews may be less rigorous or only include the classic item analyses (rather than more robust and rigorous analyses that are possible). However, if you’re going to draw any inference from the results of an evaluation there should be some regular review, even if infrequent. Don’t skip this entirely.

The key to understanding psychometrics is that the choices you make influence the conclusions you can draw based on the outcome of the evaluation. Reducing rigor at any point in the process may result in quality issues (e.g., questions or entire evaluations that are technically inaccurate, out of date, or irrelevant). Most IT certification exams are developed with the goal of creating the highest quality questions and, as a result, have steps in their design and development process to ensure that quality, but these steps add cost, time to market, and complexity to the process. And that cost and effort may be wasted unless a corresponding level of rigor is applied to the delivery and maintenance of the exams.

Psychometrics is something everyone should care about if you or someone you love needs to take an evaluation of any sort. It’s through psychometrics that we ensure an evaluation is valid, reliable, fair, and meaningful. You want someone like me watching over their design, development, delivery, and maintenance processes.

Thanks for joining me on this journey. I hope you learned something—even if it is that the driver’s license test may not, in fact, be a very good test from a psychometric perspective (although if the driving test is required in your state, it may be a bit better). Let’s just say that my psychometric knowledge of question writing may have helped me pass the WA state driver’s license test when I moved here… I probably shouldn’t be telling you that…