Written by Emmett Dulaney

Several years back, I toyed with the idea of going back to school and pursuing a law degree. I was serious enough about it to take the LSAT (Law School Admission Test), which is a prerequisite for applying to law school. The thing that struck me most odd about the experience was the range of scores possible on the LSAT. The range is from 120 to 180 and, at the time, I joked that this was so the most unprepared candidate could say with a straight face that they only got a 120 and those not knowing the range would assume this to be better than it actually is.

I did not end up pursuing the law degree but found myself with questions of why certification vendors use the range and score combinations on exams that they do. While some will use a range that starts with zero (typically 0 – 1000), it is not uncommon for the range to start at 100 and go to 500, 700, or 900. While some of the reasoning behind doing so may be to allow candidates to save face when they fail and not look like complete duds to their employers (who may be paying for the exams), far more has to do with exams using scaled rather than raw scoring.

Raw scoring is the simplest method of grading an exam. It simply sums the total number of points earned and compares that score to a raw cut score (the number of points needed to pass). Sometimes this is presented as a percentage correct, dividing the points earned by the total points possible. For example, if our company wants to assess how well exam candidates understand ABC software, we can write 100 questions about the features of the software and award our certification to anyone who answers 75 or more correctly. At the conclusion of the exam, we can either report that the candidate “passed” and provide no additional score information, or we can report that the candidate obtained 75%, or 75 points out of 100. However we report it, we’re using a raw score to indicate they reached or exceeded an established threshold and therefore should be granted the certification.

Raw scoring introduces a few issues that most people outside the testing industry may not realize.

First, if you use best practices to set the cut score rather than arbitrarily picking a number, you will have to deal with expectations for what a raw score means. You may find various stakeholders for your exam – from test-takers to your company’s marketing managers – voicing opinions that the cut score is too high or too low based on their experiences with getting grades in school. They may even exert undue influence based on their expectations. As an example, if someone sees that the score to pass is 65%, they may equate that to getting a D in school…not a grade a person would feel proud of. But in the context of your exam and the difficulty of the questions in relation to the target audience, such a score may be perfectly appropriate. Conversely, if the difficulty of the test sets the cut score at 80%, candidates who score in the 70s may expect to pass and complain loudly when they don’t. You may want to carefully consider how well your stakeholders’ perception of the raw score reflects the reality of your testing program.

A more substantial problem with raw scoring emerges when different combinations of questions are presented to different candidates. For example, for security reasons you may create a large item pool and randomize which questions are selected for each topic. This makes it harder for unethical candidates to simply memorize a small set of answers. But the more different sets of questions you create, the harder it becomes to ensure that each set has the same difficulty. It is obviously unfair to use the same raw passing score for the candidate who saw the more difficult set as you use for the candidate who saw the easier set. You’ll get candidate confusion and complaints.

A related issue is how maintaining the exam can impact the difficulty of an exam. Adding, deleting, and editing questions can cause the difficulty of question pools to drift over time. If you’re using raw scoring, you could compensate by changing the cut scores. For example, if the evolved set of questions are easier than the original set, you might adjust the passing score from 70% up to 75%. But then you’d have to explain to new candidates why they have to take what they might assume to be a harder test. Conversely, if you kept the same cut score, you’d be lowering your standards, allowing unqualified candidates to obtain the certification.

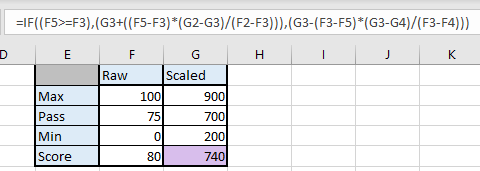

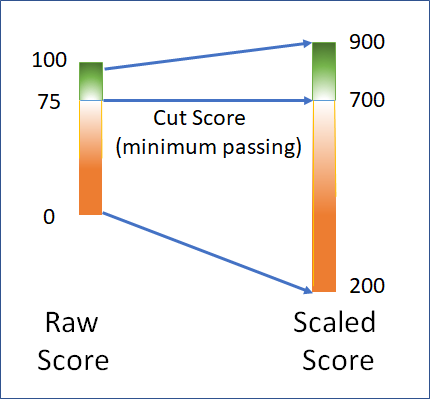

An option is to use scaled scoring, calculated by doing a simple mathematical conversion of the raw scores onto a common metric. The raw cut score is equated to the desired point in the scaled score range, then all the raw points above the cut score are evenly distributed to the top end of the scaled score range and all those below it are evenly distributed to the bottom. See Figure 1 as an example. This program has a scaled score range of 200-900 and has set the scaled passing score for all exams to 700. One of their exams is a 100-point exam with a raw passing score of 75. To produce the scaled score, 75 would be equated to 700, 100 would be equated to 900, and the points from 76-100 would be evenly distributed from 700 to 900. Similarly, 0 would be equated to 200 and the points from 0-74 would be evenly distributed from 200 to 700 on the scaled score range. In this example, the score reported to candidates who achieved a raw score of 80 would receive their scaled score of 740, since 740 is above the scaled cut score by 20% of the difference between the scaled cut and maximum scores.

Using scaling will allow you to make fair comparisons between candidates and between different attempts by the same candidate, even when their exams contain varyingly difficult sets of questions. It has the added benefit of enabling the test publisher to communicate the same passing score across all of their certification exams, reducing complexity and confusion.

Before leaving this topic, I’d like to mention another situation in which scaled scoring can help smooth communication. During the evolution of a released exam, it is very useful to test and statistically evaluate potential new questions. One way to do this is to include a few new questions in live exams, but not factor them into a candidate’s score. It is critical that the candidates be unable to identify the unscored questions so that they treat the unscored questions the same as the “real” questions. Otherwise the evaluation wouldn’t be valid. By using scaled scoring you can include unscored questions in live exams without overcomplicating communication with the test takers.

So, the next time you hear discussions about unusual scoring on an exam you will be able to provide a little clarity. And this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to scoring, there’s lots more to discuss… like just how is the raw cut score established fairly for different sets of questions? Stay tuned for more.

Emmett Dulaney is a professor at a small university and the author of several books including Linux All-in-One For Dummies and the CompTIA Network+ N10-008 Exam Cram, Seventh Edition.